Does Height Matter?

Wainwright versus Rutland: why modest hills are a match for mountain wonder

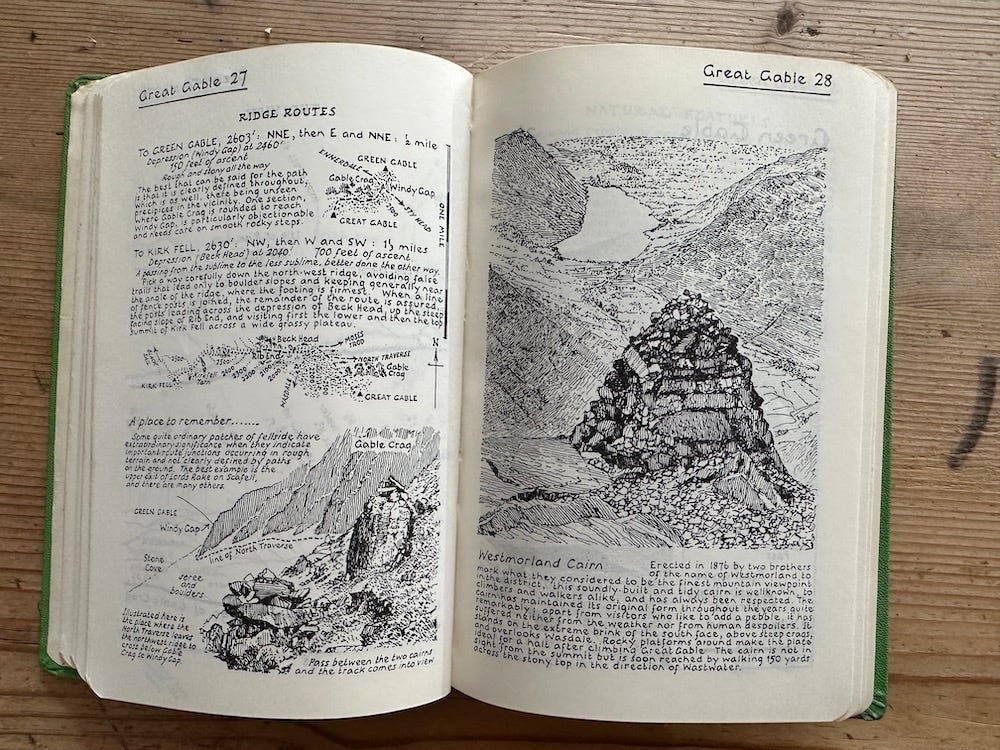

Thirty years ago, as a young journalist at Country Walking magazine, I was dispatched to Cumbria to write a cover feature about Alfred Wainwright, the author and illustrator of the exquisite, hand-drawn Pictorial Guide to the Lakeland Fells series.

Wainwright himself had died in 1991 but a new biography by Hunter Davies had been published, including revelations of the love affair that had brought A.W. and his second wife, Betty – his secret ‘dream girl’ – together.

I had requested an interview with Betty and while she didn’t wish to be quoted in my article, she agreed to meet me at her home, a comfortable bungalow outside Kendal.

As she made tea for us, I admired the views of the fells from the large picture window in the living room, under which sat a bust of Wainwright.

We chatted about A.W., his work and their life together. Betty was generous with her time and responses and shared with me some treasured photographs. In her early seventies, she was petite and sparkled with life.

After the feature was published, she sent me a handwritten note thanking me for the article. I had dared to state my preference for the softer, rounded hills of the Sussex Downs, my home county, to Lakeland’s rugged fells. While of course she loved the Cumbrian landscape, she was also wary of the sycophancy attached to her husband and his work, and thanked me for presenting, “a balanced view.”

Back in the Country Walking office, my southern perspective was seen as heretical: the Lake District was the number one destination for our readers. Our best-selling issues were always those which featured a cover photograph of the Lakes.

My editor despaired at me banging on about lowly downland being superior to mountain peaks for walking. After all, who didn’t aspire to bagging one of the 214 English ‘Wainwrights’ – all but one of which is more than 1,000ft (305m) high – or a 3,000ft (915m) Munro in Scotland? Height, it seemed, mattered.

But from my modest viewpoint, while Cumbria is evidently naturally beautiful, some of the steep-sided valleys and mountainous walls of rock could also be harsh, intimidating, claustrophobic even.

By contrast, the bare chalk grasslands of the South Downs, which are easily accessible on foot, are rounded and soft, with domes and ridges, and tight, springy turf. There is a temptation is to walk barefoot into the landscape – and I have happily wandered bootless, feeling fleshy grass and trampoline turf underfoot.

Ditchling Beacon, at 814ft (248m), provided ample thrills when I was young, the steep northern escarpment overlooking the Weald contrasting with the long southerly slope down towards distant Brighton and a glittering sea beyond.

While there is an undoubted and exceptional thrill to standing atop a mountain peak, there can also be the daily, obtainable pleasure of far more modest hills.

I was reminded of this while walking above the Welland Valley at Seaton recently, returning to a favourite spot with a 360-degree view of Rutland. (See below for a video of a walk from Morcott to Uppingham.)

Walking towards the western end of the village, past The George and Dragon and beyond the village hall, there are steep and tempting steps built into a stone wall leading up to a grassy sheep paddock.

Patches of uncultivated calcareous grassland are few and far between in Rutland, but this field is a joy to walk through, its closely woven turf yielding underfoot like springy downland.

Following the footpath north across the pasture, you enter a wide, open cultivated field and a track much used by village dog walkers. It’s there, at the summit of the limestone ridge that the view opens out into a magnificent panorama.

Facing north, on the opposite ridge, is Glaston, strung out along the main road. Turning slowly anticlockwise, Bisbrooke, on a humpback between two narrow stream-cut valleys; beyond, the high and mighty spire and roofs of Uppingham. The castle village of Rockingham and the wide hollow of the Welland is away to the west, while Gretton clings to the valley side to the south. Finally, more or less at eye level, is the tip of the spire of Seaton church itself, reminding me of my elevated position.

I like to think this is one of the finest views in Rutland as it is accompanied by an airy sense of freedom and the faint possibility that your feet might momentarily leave the ground. This sensation comes as a natural high and I can lose myself entirely despite the ascent being limited to a modest limestone wold rather than a Lakeland fell.

There’s no need to climb a mountain when exhilaration is within walking distance of the front door, it would seem.

The naturalist W.H. Hudson made this point and the sensation of, “sudden glory,” in his book Nature in Downland (1900):

“It is, I think, a very common error that the degree of pleasure we have in looking on a wide prospect depends on our height above the surrounding earth – in other words, that the wider the horizon the greater the pleasure. The fact is, once we have got above the world, and have an unobstructed view all round, whether the height above the surrounding country be 500 or 5,000 feet, then we at once experience all that sense of freedom, triumph, and elation which the mind is capable of.”

There are places around Rutland that, while not closely resembling downland, remind me of the hills of home.

And while I’m sure the great Alfred Wainwright would not have been moved by the argument that modest hills could match mountain wonder, the ‘sudden glory’ of this Welland Valley panorama above Seaton is enough to lift my spirits to lofty heights.

A lovely piece Gary and l agree, chalk downland is unbeatable.

A really enjoyable read, and an inspiring , relaxing video, highlighting the treasures of Rutland area. I’m looking forward to walking around Rutland Waters with Katie when I next visit . Something to look forward to and enjoy. We are both blessed living in lovely, surroundings.